Kei Whea Te Tuna?

Do you remember the first time you saw a freshwater eel? Some shudder at the thought while others enthuse about their beauty and grace and it can certainly feel like a blessing to be lucky enough to be able to dive with one. In this blog we will talk a little more about these incredible and mysterious creatures and understand some of the threats they currently face.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The first Polynesians to arrive in New Zealand must have been shocked to find themselves dwarfed by the mighty Moa. But lurking in the depths of the rivers and lakes were more giants – snakelike fish they called "Tuna" that would grow to the width of a man’s thigh, up to two meters long, and can live for more than a hundred years. Eels became an important food source for Māori, but it was a relationship that extended beyond nourishment to respect, and even reverence. Over time they were even thought of as protectors or guardians of our rivers, lakes and oceans.

Tuna kuwharuwharu (longfin eels) are of great significance to Maori culturally, nutritionally and economically. Eels are a significant mahinga kai (food) for Maori, although the dwindling numbers have seriously affected the significance of eels to their diet. They are also used by some iwi as an ecological health indicator to assess water and habitat quality.

There are many traditions as to the Tuna's origins and songs dedicated to eels, which reinforces their importance to Maori. In one tradition, Tuna came from Puna-kauariki, a spring in the highest heavens. The families in the spring were Para (frostfish), Ngōiro (conger eel), Tuna (freshwater eel) and Tuere (hagfish or blind eel). The waters of the heavens dried up, and this group made their way down to Papatūānuku (the earth). Tuna remained in fresh water, but Para, Ngōiro and Tuere all went to the sea.

In another story, Tuna, a giant eel, frightened the wives of the demigod Māui. As punishment, Māui cut Tuna in half. One half landed in the sea and became the conger eel. The other half fell in a river and turned into the freshwater eel.

Maui Attacks Tuna

Early Maori understanding (matauranga) of eels came from from extensive observation and interactions so that they could understand the life cycle, habitat requirements and migratory routes in order to enable the sustainable take of the population. Eeling would also take place at “special times of the month and year according to a range of environmental indicators including lunar cycles. Maori developed sophisticated trapping methods, such as hinaki (eel pots), pa-tuna (eel weirs), patu tuna (eel striking), toi (eel bobbing without hooks), koumu (eel trenches), korapa (hand netting) and mata rau (spearing). Eel weirs were also commonly used, however the arrival of European settlers and their desire to make waterways more navigable saw the interruption of the use of eel weirs.

Types of eel.

At first glance, all New Zealand freshwater eels look the same, but there are three species being the Shortfin, Longfin and spotted eel.

The Longfin eel (Anguilla dieffenbachii) is only found in New Zealand and its conservation status is unfortunatley classified as "At risk - declining". The shortfin eel (Anguilla australis) can be found in New Zealand, Australia and some pacific islands. The spotted eel (Anguilla reinhardtii) which also lives in eastern Australia was first confirmed in New Zealand waters in 1997, and is currently only found in rivers from Taranaki to Northland.

So how do you spot the difference between the two main species of freshwater eel found in New Zealand? On a longfin eel, the dorsal (top) fin extends a lot further forward than the anal (bottom) fin and they are coloured dark brown and black. Longfin eels can be found throughout both the north and south island, including in high-elevation lakes and rivers.

The dorsal fin of a shortfin eel only extends a little further forward than the anal fin and they are coloured light brown and olive. Shortfin eels are more often found in lowland areas like marshes and wetlands.

Eels of both species will take up residence in a particular part of the lake or stream or marsh, and then spend their time doing the usual things eels might do, hanging out under a bank, rocks or in the vegetation, the larger ones eating everything from fresh-water crayfish to rodents, ducklings and fish. Small (less than 50-centimetre) longfin and shortfin eels generally feed on snails, insects, worms, grubs, crayfish and small fish. Eels feed mainly at night, using their excellant sense of smell to track prey. Their protruding tube-like nostrils help them to get a good scent of what’s in the water. Once the eel is close, taste buds on its head and sensors along its sides help locate the food.

Growth rates of eels are slow. Longfin eels grow at around 2.5 centimetres a year at a length of 30 centimetres, and they slow down to only 1.5 centimetres a year at a length of 1 metre. Shortfin eels grow a little faster. These slow rates are a result of temperature, food supply and competition. Longfin eels live for a very long time and the lifespan is thought to be anywhere between 20 - 60 years. It is thought that female Longfins can live for up to 100 years.

Did you know Longfin eels are able to travel overland for up to 2 days by breathing through their skin and can even climb vertical surfaces?

So far, so normal. But when it’s time to breed, things get weird.

Spawning on the High Seas

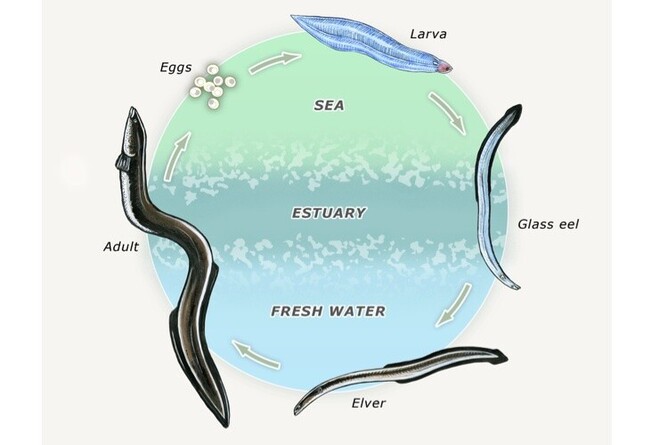

Freshwater eels evolved from tropical marine ancestors near present-day Indonesia, so all 19 freshwater eel species return to the sea to breed. Freshwater eels have a remarkable life cycle, which begins and ends in the ocean although spawning has never been observed and much is unknown. It is thought that spawning might take place at depth in warm waters, possibly somewhere between New Caledonia and the Tonga Trench. This migration to the tropics to breed is a journey that takes about 5 to 6 months. New Zealand’s Shortfin eels produce 1.5 - 3 million eggs, and the Longfins 1 - 20 million eggs.

We might not know exactly where the eels spawn, but we have a general sense of what happens next. For the adult eels, it’s game over. All eel species are semelparous, meaning they breed only once at the very end of their lifecycle. Males fertilise the eggs. After spawning, the adults die. The eel larvae spend between 7 to 10 months at sea. At this stage they have teeth, but it is not clear for what purpose - they may store calcium for bone development. Their skin may absorb nutrients, as researchers have not found food in the larvae. Eventually they drift back towards New Zealand on the currents. At this stage in their lifecycle they’re called leptocephalii, which means “leaf-shaped head” in Latin.

Once the larvae reach land, an extraordinary transformation takes place: they become slender, transparent eels, known as glass eels. They arrive at New Zealand’s coast from July to December, with numbers peaking in spring (August–October) – the time of whitebait migration. Gradually they acclimatise to the freshwater before swimming upstream. Glass eels then migrate into river mouths or estuaries in astounding numbers.

The little eels stay in the lower reaches of the rivers until summer, around January or February, before making another push upstream. Scientists discovered that the eels choose their route by following the scent of their own species upstream. Once in freshwater, the glass eels develop into juvenile eels, or elvers, and take on their dark coloration.

Elvers eventually become adults, with bigger heads and fatter bodies. Shortfin eels tend to stay in the lower reaches of a river, also inhabiting swamps and wetlands. But the longfins keep migrating upstream, year after year, to the high elevation lakes and rivers. Once they find suitable habitat, they take up residence in one spot and stay there for many years. After many years in fresh water, eels migrate back down the waterways to the sea and the cycle begins again.

When they reach breeding size, eels change from ‘yellow-bellies’ to ‘silver-bellies’. The yellow-grey underside becomes grey-white, the head shape changes and the head, back and pectoral fins darken. Shortfin males migrate in February–March, and longfin males in April. The females soon follow, with both males and females dying after spawning. Studies have shown that the species also migrate at different ages. Unfortunetly human habitation has created problems for this incredible journey, building barriers across waterways which have hampered their route. One estimate suggests that hydroelectric dams have blocked the longfin eel’s access to the sea in 35% of its natural habitat.

In another strange twist, eel sex isn’t determined genetically, but by environmental conditions, much like sea turtles. Instead of temperature, the eels respond to the local environment and density of other eels. The more eels there are on a particular stretch of river, the greater the percentage of males in that population.

At a certain point in the lifecycle, the environmental and physiological cues trigger the eels to begin their final migration back to the sea to breed. It is not fully understood what determines the switch, as the timing isn’t strictly tied to age, but more to the eels’ health, body condition, and energy reserves. Only healthy eels will survive swimming thousands of kilometres back to tropical waters.

Eels in decline and threats

While Longfins are still relatively common their numbers are sadly in decline due to a number of factors. The longfin eel is now ranked as ‘At Risk - Declining’ according to the New Zealand Threat Classification System listings (2014).

New Zealanders showed an interest in the longfin eel as a commercial fishery until the 1960s when commercial catches rose steadily. Fishing numbers increased well into the 1970s when it became apparent that significant stock numbers were reduced. By 1975, eels were the most valuable fish export after rock lobsters. Five years later, they were the fifth most valuable finfish export.

Drainage, hydro development, irrigation schemes and river diversions also affected eel numbers by reducing their habitat. In addition to this culverts and dam construction impeded and prevented their natural migratory routes.

Water pollution has also had a huge impact on eels. Farm industry sewage and effluent from discharged into rivers and nutrients leaching from soils into waterways has resulted in large quantities of oxygen being removed from the water. The result of this oxygen depletion is that the eels will either die or move away. Toxins in the water such as minerals and hydrocarbons from mining can also kill eels.

Eels have always played an important role in Maori culture. As a consequence, they have built up a rich folklore and understanding about eels resulting in them featuring in Maori traditions, art and literature. Many marae are adorned with carvings of Eels alongside their ancestors. They were heavily relied upon by Maori as a source of food (kai) and important events were often scheduled around the harvesting of eels. They were and still are the kaitiaki (Guardians) of our streams, rivers and lakes and for that reason alone we should do more to ensure their survival into the future that way ensuring future generations can observe and enjoy these incredible creatures..

We regularly have some great interactions with the Longfin eels during dives in our local lakes and if you have not seen one for yourself, maybe it's time to take a dive with us?

Contact us today about joining our dive club and we will do our best to put you in the water with one of the mysterious eels of Aotearoa.

Below is a video captured during a recent Mares Horizon XR SCR training course by Chris Serfontein (Mares/SSI Australia), May 13th 2022.